Taxbuzz | Vivad se Vishwas Scheme – Opportunity to settle tax disputes, now or never…

- Vivad se Vishwas Scheme (‘the Scheme’) was announced by the Union Finance Minister Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman in her budget speech on February 1, 2020.

- The Scheme aims to – (i) settle pending direct tax cases (around 4,83,000 cases) before various forums; (ii) generate timely revenues; and (iii) save time and energy to taxpayer and the Government.

- The Scheme broadly provides for payment of certain portion of disputed demand/ tax, with complete waiver of interest and penal consequences.

- The key/ salient features of the Scheme (namely Direct Tax Vivas se Vishwas Scheme, 2020 as passed by Lok Sabha on March 4, 2020) are as under:

• Eligible taxpayers under the Scheme:

Following taxpayers shall be eligible to avail the settlement/ benefit under the Scheme:

– Where appeal or writ or SLP filed by assessee or Department is pending as on 31.01.2020;

– Orders where time limit for filing appeal has not expired as on 31.01.2020;

– Case pending before DRP as on 31.01.2020 as well as cases where DRP had issued directions on or before 31.01.2020 but final assessment order has not been passed;

– Revision petitions pending before CIT under section 264 on 31.01.2020;

– Search cases where disputed tax is less than Rs. 5 crore (assessment year wise);

– Cases pending in arbitration in India or abroad.

Exclusions from the Scheme:

– Assessment year(s) of search cases if disputed tax is more than Rs 5 crore.

– Years in respect of which prosecution instituted under the Income tax Act on date of declaration.

– Tax arrears relating to undisclosed foreign income and assets.

– Tax arrears based on information from foreign countries as per section 90 or 90A.

– Persons against whom prosecution instituted on date of declaration under IPC or the Unlawful Activities Act, NDPS Act, 1985, PC Act, 1988, PMLA, COFEPOSA, Prohibition of Benami Property Transactions Act, 1988 and Special Court Trial in Securities Act, 1992.

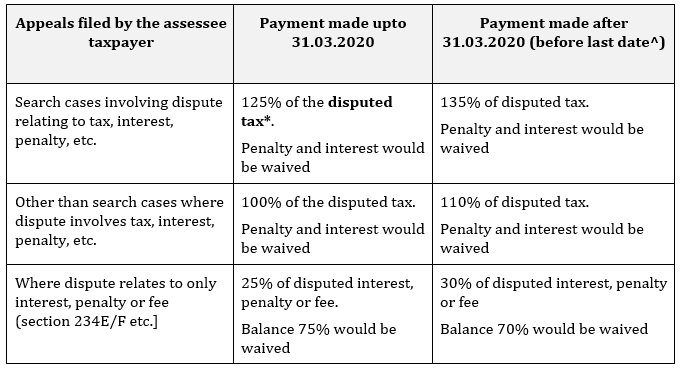

• Payment to be made under the Scheme:

^ last date to be specified by Central Government (tentative- 30.06.2020)*Disputed tax (including cess and surcharge)

a. Where any appeal, writ or SLP is pending before the appellate forum- amount payable as if such appeal or writ or SLP was to be decided against the assessee.

b. Where assessment order or order in appeal or writ has been passed and time limit for filing appeal or SLP has not expired as on 31.01.2020- amount of tax payable after giving effect to the order so passed.

c. Where objection filed is pending before the DRP- amount of tax payable if DRP was to confirm the proposed variations.

d. Where DRP has issued direction under section 144C(5) and the final assessment order is yet to be passed as on 31.01.2020- the amount of tax payable as per the final assessment order to be passed by the assessing officer pursuant to DRP directions.

e. Where revision application under section 264 is pending- amount of tax payable if such application was not to be declined.

f. Where enhancement issued by CIT(A) before 31.01.2020, disputed tax shall be increased by amount of tax pertaining to issues for which enhancement notice issued.

– Where dispute relates to reduction of loss or depreciation or tax credit under section 115 JAA or section 115D, option to the assessee either to:

(i) pay notional tax and carry forward related tax credit or loss or depreciation; or

(ii) forego the disputed credit or loss or depreciation without paying any tax.

– 50% of tax payable in following cases:

(a) Disputed tax relating to appeal/ writ/ SLP filed by the Department

(b) Issues on which there is favorable decision by ITAT/ HC.

– No tax payable on issue covered by SC in assessee’s own case

• Procedure under the Scheme:

– Assessee to file declaration in specified form before the Designated Authority (DA).

– Taxpayer to furnish an undertaking waiving his right to seek or pursue any remedy.

– DA to determine amount payable and grant a certificate within 15 days.

– Declarant to pay the amount within 15 days from the date of receipt of the certificate.

– Upon filing of declaration, pending appeal is deemed to have been withdrawn.

– Taxpayer to submit the proof of withdrawal of appeal or writ with intimation of payment.

– Appellate forums, arbitrator, conciliator or mediator shall not decide the issue in respect of cases where an order under clause 5(1) is passed by the designated authority.

– Amount paid in pursuance to the Scheme shall not be refunded under any circumstances

Clarifications/ Comments:

– Declaration form is to be filled assessment year wise, i.e., one declaration form for one year.

– Tax determined by DA – not appealable [FAQ No.47 of Circular 7/2020].

– DA has power to rectify patents errors in order/ certificate [FAQ No.46 of Circular 7/2020].

• Other important features of the Scheme

– Immunity from prosecution.

– Issues settled not to be concerned as any precedence

– If substantive addition is settled, protective addition shall go [FAQ No.35 of Circular 7/2020].

– No impact of settlement of TP adjustment on secondary adjustment made under section 92CE.

• Clarifications/ Comments:

– Draft order passed but no objection before DRP to await final order to file appeal before CIT(A): Assessee may opt for the scheme and pay tax as determined in the draft order.

– Disputes pending in AAR – Not covered.

– Writ pending against AAR ruling – Covered, with disputed tax to be computed as per AAR order [FAQ No.3 of Circular 7/ 2020].

– Issue set aside to the file of the assessing officer with a specific direction – Covered but assessee to also settle other issues arising in same appeal [FAQ No.7 of Circular 7/2020].

– Quantum appeal settled, penalty automatically deleted [FAQ No.8 of Circular 7/2020].

– Penalty appeal cannot be settled independently if quantum appeal also pending.

– Writ against 147 notice:

(a) Reassessment order not passed – Not covered [FAQ No.7 of Circular 7/2020].(b) If reassessment order passed – Covered (explicit clarification awaited).

– Issue wise settlement not possible – Entire appeal to be settled [FAQ No.14 of Circular 7/2020].

– Department appeal against ITAT order quashing assessment – 50% of disputed tax payable [FAQ No.14 of Circular 7/2020].

– Excess tax already deposited – to be refunded without any interest.

– Disputed tax to be computed considering rectification order passed by assessing officer.

– Option available to settle assessee and/ or departmental appeal [FAQ No.40 of Circular 7/2020]

– If TDS dispute is settled by the deductor, the deductee shall get the corresponding credit of taxes as on the date of settlement of dispute [FAQ No.30 of Circular 7/2020].

– On settlement of appeal against order u/s 201 (TDS default), no amount payable for settlement of issue relating to consequent disallowance u/s 40(a)(i)/(ia) [FAQ No.31 of Circular 7/2020].

– Where deductee settles dispute in respect of income on which TDS not deducted, deductor would not be required to pay TDS amount but only interest u/s 201 (1A). Deductor may also chose to settle the issue of such interest under the Scheme [FAQ No.32 of Circular 7/2020].

VA Comments and Open issues:

- The Scheme is a welcome opportunity to settle pending disputes and claim completed waiver of interest and penal consequences.

- In cases where disputed issues result in variation of loss, and the resultant loss has not actually been or is not likely to be set off in subsequent year(s), assessee may definitely consider getting the appeals settled under the Scheme.

- In cases where the dispute in appeal has the effect of reducing the loss returned by the assessee, the Taxpayer has the option to either – (i) pay tax computed on notional basis on the issue in dispute and carry forward the loss; or (ii) forego carry forward of disputed amount of loss without paying tax computed on notional basis.

- Where appeal of the Department is pending and the assessee choses option (i) above, the assessee shall be liable to pay half (50%) of the principal tax amount; however, if the assessee choses option (ii) 50% of losses shall be forgone and balance would be allowed to be carried forward (clarification awaited).

- In FAQ No.37 in Circular 7/2020, it has been clarified that if the issue is decided in favour of the assessee by the SC, the disputed tax in respect of such issue shall be considered as Nil. The said benefit should also be extended to cases where issue is in favour of the assessee by the High Court in own case, against which no appeal is filed by the Revenue.

- In case rectification applications pending before the assessing officer are not disposed off judiciously and quickly, the assessee may be forced to pay excessive tax.

- In certain cases, while the appeal of the assessee was pending as on specified date (31.01.2020), but the same is disposed off by the appellate authority after the specified date in favour of the taxpayer, 50% of disputed tax (and not 100%) should be payable.

- Considering that the Bill/ Scheme is yet to be enacted and rules/ forms, etc., are still to be notified, the deadline of 31.03.2020 for payment of disputed tax appears to be highly ambitious.

For any details and clarifications, please feel free to write to:

Mr. Rohit Jain : [email protected]

Mr. Deepesh Jain : [email protected]